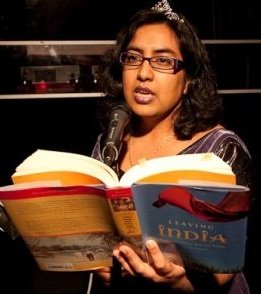

credit: PRESTON MERCHANT

From Chapter 1, Water: The lake of nails is where your history begins…

Listen at NPR (audio) | Read at Amazon.com “Look Inside”

From Chapter 4, Salt: When my grandfather was released from jail…

Read at India Currents

From Chapter 7, Shelter: Los Angeles was runway lights shimmering against the dark glass skin of hotels… Read at Colorlines

From Part IV, Destiny:

IT IS OCTOBER AND THE WOMEN are dancing. All around the world we put on our long skirts and tight bodices, wrap ourselves in gauzy shawls, fasten jewels at our throats and bells around our ankles. We dance barefoot in temples, where we have temples; or community centers, high school gymnasiums, even bare fields. The dance is what remains the same: a sacred circle.

Garbaa, the word for the Gujarati folk dance, comes from a Sanskrit root, grb, for womb. Round and round we twirl to celebrate Navratri, the lunar festival of nine nights of dancing in honor of the goddess. I have danced the garbaa with my cousins at a newly erected temple in New Zealand, where Indians are running more and more corner stores (“dairies”) and clustering together in new neighborhoods. In Fiji, I have danced it with my aunts at a temple whose walls slide away to let in the tropical night. I have swirled and sweated it with relatives and friends in London, New York, Toronto. And as a child in Michigan, I twirled round a fluorescent-lit multipurpose room in the Plymouth Cultural Center, whose hallways we shared with white-robed tae kwon do students and bulging ice hockey players.

Always it is the cusp of seasons: harvest, or planting. The soundtrack booms from live singers and musicians, or only a precious cassette tape (now CD) brought over (downloaded, bootlegged) from the old country. Always the oldest women cluster around the edges, on bleachers or folding chairs or the floor, gossiping or watching silently as they clutch knees and hips long past dancing. Every generation has its place, and gives way to the others. Middle‑aged women form the outer ring, moving slowly to the 3/3 beat, clapping their hands three times: once at the earth, once at the waist, once at the sky. The circle advances, counterclockwise. In an inner ring, younger women and girls who are just becoming women show off fancier moves; wrists and hips swivel with a grace and vanity befitting their age, as if they know that this is their time on earth. At the very center, the littlest girls run around and groove to their own beats, wild foals dressed up for a few nights as princesses.

My great-grandmother, Maaji, harvesting betel leaves in Fiji. For more images, see the Leaving India slideshow.

At midnight we chant the praise‑song of prayer. We pass around a tray with the small flame whose grace we accept one by one; we make offerings of coins and bills; we share the sanctified food. Then we emerge sweating and sated, bundling up in winter coats to cross the tarred parking lot, or walking down hot dusty lanes to an ancestral home.

If diaspora is defined by the phenomenon of dispersal, then bringing together the stories of a diaspora may be a task as wisely undertaken as that of piecing Humpty Dumpty back together again. And trying to look into our diaspora’s future… can feel like examining a cracked mirror. It can never be fused into smooth glass again; better, perhaps, to construct a mosaic.

But what is it that glues us together, across time and space? Each generation grapples with a new set of circumstances, inheriting some traditions and discarding others. The choices of what to change and what to continue are made not once and for all, but daily, yearly, life by life. What, then, is the fabric of the shared identity that seems to persist, though in places it frays? Is it still, after so many generations, India—or the memory of India?